It was America’s first widespread influence peddling scandal that involved about a dozen members of Congress. And it cost the US Treasury at least tens of millions of dollars in fraudulent costs. It was a scenario that has played out dozens of times throughout American history.

Using the power of their votes, members of Congress accepted bribes in return for benefitting the well-connected. And themselves. The scandal became public 150 years ago, but the actual fraud began ten years earlier.

Perhaps in a surprise to very few, despite widespread public outrage no member of Congress was seriously punished for their role in the scandal.

The steam locomotive made its debut in England in 1804. It quickly began to overtake horse-drawn carts on rail as a more effective method to move goods. Steam locomotives were being used to connect English cities, first with goods and then with people. By the 1820s, the steam locomotive had become the most efficient way to transport passengers.

The earliest steam locomotives in the United States were imported from England. Chartered in 1827, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad became the first locomotive company in the US. B&O was an attempt to compete with the use of canals and inland waterways to navigate trade routes to the West. By May 1830, the B&O was up and running with its first section of rail open for business. Other railroads began to appear and, over the next two decades, track was being laid and steam locomotive-driven trains were being added throughout the East Coast.

Westward expansion in America was occurring throughout the middle of the nineteenth century. However, travel to the West Coast was time-consuming. Many travelers would take the months-long trip by ship around the southern tip of South America. Crossing the western mountain ranges and the great prairies was deemed impractical and dangerous.

Congress wanted to shorten the time needed to travel from coast to coast. It enacted the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, which was intended to incentivize private construction of a nearly 1,800-mile, transcontinental railroad and a companion telegraph line. The 32nd parallel was designated as the route and there would be generous land grants for rights-of-way. The Central Pacific and the Union Pacific were the two companies selected to complete the construction. The Union Pacific was capitalized with $100 million from the federal government. In addition, the Railroad Act created financial incentives for each mile of track laid by each company.

In 1863, the Central Pacific began building from Sacramento eastward and the Union Pacific started building westward from Omaha. The two railroad companies would eventually meet at Promontory, Utah, in May 1869 when the ceremonial final spike was driven into the track to commemorate linking the two rail lines.

In May 1864, the directors and major shareholders who chartered the Union Pacific also chartered a duplicate company named Crédit Mobilier of America, but the participation of the same people in the two different companies was kept secret. Union Pacific officials claimed Crédit Mobilier was a separate entity hired by Union Pacific as the general contractor to build the rail line. In reality, the business relationship was an elaborate scheme for shareholders of Union Pacific to shield themselves from the financial risks of the Union Pacific and to guarantee themselves profits from Crédit Mobilier.

Crédit Mobilier would charge Union Pacific exorbitant costs and fees to build the railroad. Union Pacific would add a modest profit to these invoices and pass them on to the federal government for reimbursement. Because the officers and directors of Crédit Mobilier and Union Pacific were the same, Union Pacific would attest that the Crédit Mobilier charges were legitimate.

The remaining challenge was to ensure Congress kept appropriating funds to continue funding Union Pacific. This was accomplished in November 1866, when Union Pacific replaced president Thomas Durant with Oliver Ames. Oliver Ames’s younger brother was Massachusetts Republican Congressman Oakes Ames, who was an influential member of the Committee on Railroads in the US House and was the point man in Congress supervising the railroad construction effort. It was a responsibility President Abraham Lincoln personally assigned.

Shortly after Oliver Ames became the head of Union Pacific, his brother Oakes began selling stock in the highly successful Crédit Mobilier to other Congressmen below the actual trading value in return for promises to vote for legislation and appropriations favorable to Union Pacific. Ames sold stock to nine House members and two senators. He was selling to those members of Congress who were the most influential in ensuring federal dollars kept flowing. These Congressmen could immediately sell the Crédit Mobilier stock at the prevailing rate and make a handsome profit. This vote-rigging scheme continued for the next few years, until construction was completed.

Meanwhile, Crédit Mobilier shareholders were making a ridiculous amount of money, due to the dividends that were being paid. The dividends were paid in a combination of Union Pacific bonds, Union Pacific stock, and cash. In 1868, the annual dividend was 280 percent. In contrast, the government-issued bonds for Union Pacific were paying only 6 percent.

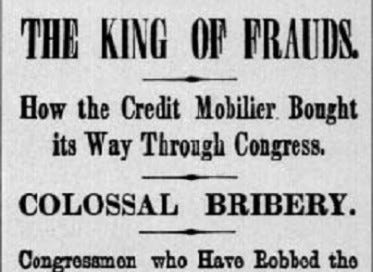

Although the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, there were simmering conflicts among the various participants for the next few years. This came to a head on September 4, 1872, when the New York Sun published an explosive story under the headline, “The King of Frauds: How the Credit Mobilier Bought Its Way Through Congress.”

The Sun published an exposé that named members of the House and Senate who were allegedly involved in the scheme. The public outcry led the House to form a special committee to investigate the allegations. A dozen members of Congress—eleven Republicans and one Democrat—were accused of having taken part in the scheme, including Congressmen William B. Allison (R-IA), Oakes Ames (R-MA), George S. Boutwell (R-MA), James Brooks (R-NY), Roscoe Conkling (R-NY), James Garfield (R-OH), and Speaker of the House James Blaine (R-ME). Senators suspected in the scandal were James A. Bayard, Jr. (D-DE), James Harlan (R-IA), John Logan (R-IL), James W. Patterson (R-NH), and Henry Wilson (R-MA). Vice President and former Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax (R-IN) was also implicated.

Nearly all of them escaped any serious repercussions. However, token punishment was meted out on February 27, 1873 when the House of Representatives censured Oakes Ames and James Brooks.

Mark Hyman is an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter, Gettr, and Parler at @markhyman, and on Truth Social at @markhyman81.

His books Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation and Pardongate: How Bill and Hillary Clinton and their Brothers Profited from Pardons are on sale now (here and here).