D.C.'s Spending Problem

The Shameful Debt We are Leaving to Our Children

Make no mistake, this failure to pass all individual appropriations measures is a two-party issue. The failure to submit a balanced budget and the passage of stand-alone appropriations measures occurred when Democrats controlled both the White House and Congress, when Republicans were in charge, and when there was divided government.

No party has clean hands.

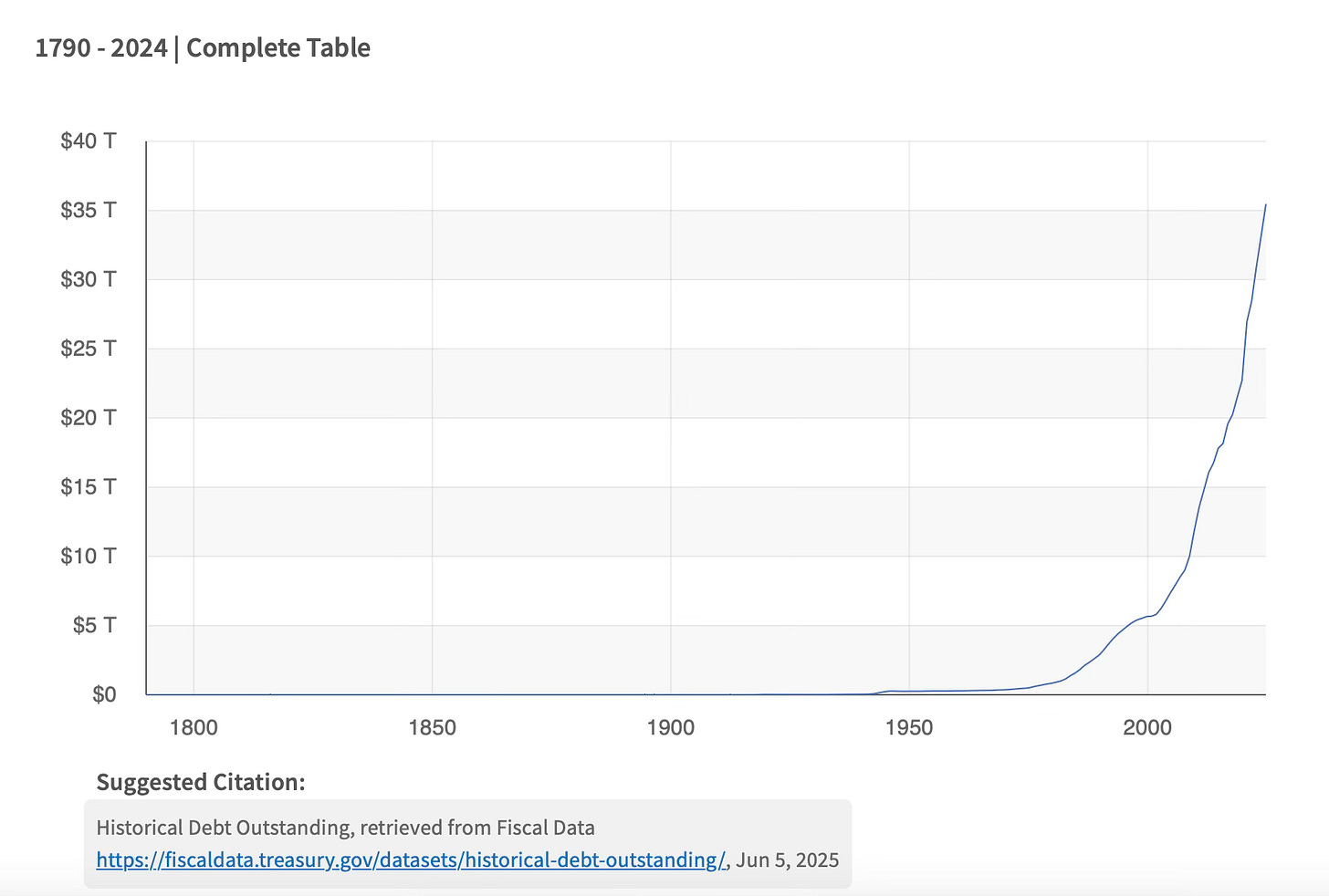

The US ended 2024 with $35.46 trillion in debt, according to the US Treasury. One of six dollars in federal spending in 2025 goes to paying interest on the debt. One hundred years ago, the federal debt was less than $400 billion. Twenty-five years ago, it was just over $10 trillion. According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, the federal debt will be more than $50 trillion by 2034, unless dramatic changes take place.

How did we get to this point?

Throughout much of the 20th century, the lawmaking process in Congress was referred to as “regular order.” The procedure in making laws was straightforward. This time-honored step-by-step process is clearly explained on the House of Representatives website:

Laws begin as ideas. First, a representative sponsors a bill. The bill is then assigned to a committee for study. If released by the committee, the bill is put on a calendar to be voted on, debated or amended. If the bill passes by simple majority (218 of 435), the bill moves to the Senate. In the Senate, the bill is assigned to another committee and, if released, debated and voted on. Again, a simple majority (51 of 100) passes the bill. Finally, a conference committee made of House and Senate members works out any differences between the House and Senate versions of the bill. The resulting bill returns to the House and Senate for final approval. The Government Printing Office prints the revised bill in a process called enrolling. The President has 10 days to sign or veto the enrolled bill.

The ideal process under regular order is that all members of Congress have the potential to be involved in the legislating process. There has been a two-century old tradition of an open amendment process, where any member may submit an amendment to proposed legislation. However, this has not occurred in 9 years.

According to the House Freedom Caucus:

For Members of Congress to represent the will of their constituents in lawmaking, they must have the ability to actually participate in making laws. No Member of the ‘People’s House’ has been allowed to offer an amendment in an open process to change legislation being considered on the floor since May 2016. The Republican 115th Congress broke the record for the most bills considered without amendments. Americans expect more from Republicans than to be mere rubber stamps, blocked from having any impact on legislation beyond voting for or against a final product.

Some might view the process of the House and Senate simultaneously considering nearly identical bills such as spending measures as slow and laborious. The flip side of the argument is it is a deliberative process, that includes negotiation and compromise, and it provides the greatest opportunity for proposed legislation to receive reasoned and well thought-out consideration.

It is also the process that provides the greatest opportunity for bipartisanship. The regular order process allowed all members of Congress to participate in formulating policy. However, not all bills would get equal consideration. Historically, committee chairs wielded tremendous power and oftentimes would decide if a bill was to receive any consideration or would merely die in committee. Members might have to wait until the following Congress to resubmit their proposed legislation. In some cases, they would have to wait years to gain enough seniority for their legislation to be seriously considered.

To be clear, regular order is not a formal process that is spelled out in House and Senate rules. Rather, it’s an understanding of a traditional process that was in place throughout much of the 20th century. Of course, regular order does not guarantee that all proposed legislation will get identical treatment. A bill that is absolutely ridiculous may never see the light of day in a committee room.

The exception to the committee approach in deliberating proposed legislation in the House is a discharge petition. A bill that languishes in a committee may be brought out of committee and to the House floor for consideration – discharged – if a majority of House members agree to it. Sometimes the mere threat of a discharge petition can get a bill moving through a committee. Still, this is a relatively rare occurrence. The last successful discharge petition was in July 2001.

The Senate has a different procedure that is unlike the House discharge petition.

Today, Congress practices irregular order. It’s nothing like regular order. It’s similar to assembling Ikea furniture without the instructions and missing the proper-sized Allen wrench. Who knows what the finished product will be?

In the last three decades or so, passing massive several-thousand page bills has become common, particularly if the same party occupies both the White House and Capitol Hill.

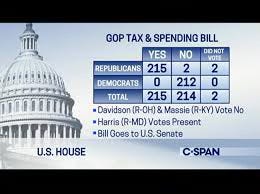

Bipartisanship for big measures rarely occurs. Let’s be honest, bipartisan is not a vote of 220 House members of one party joined by a couple of the opposing party. That’s not bipartisan is any meaningful sense of the term. There was a time when there was a more even mix of Republicans and Democrats on both sides of a bill vote. That is an extremely rare occurrence today.

There are probably several contributing reasons for this party-centric behavior in Congress. In general, liberal Republicans in the northeast became Democrats and conservative southern Democrats joined the GOP. There is probably more ideological alignment among the two parties than the US has witnessed in more than a century.

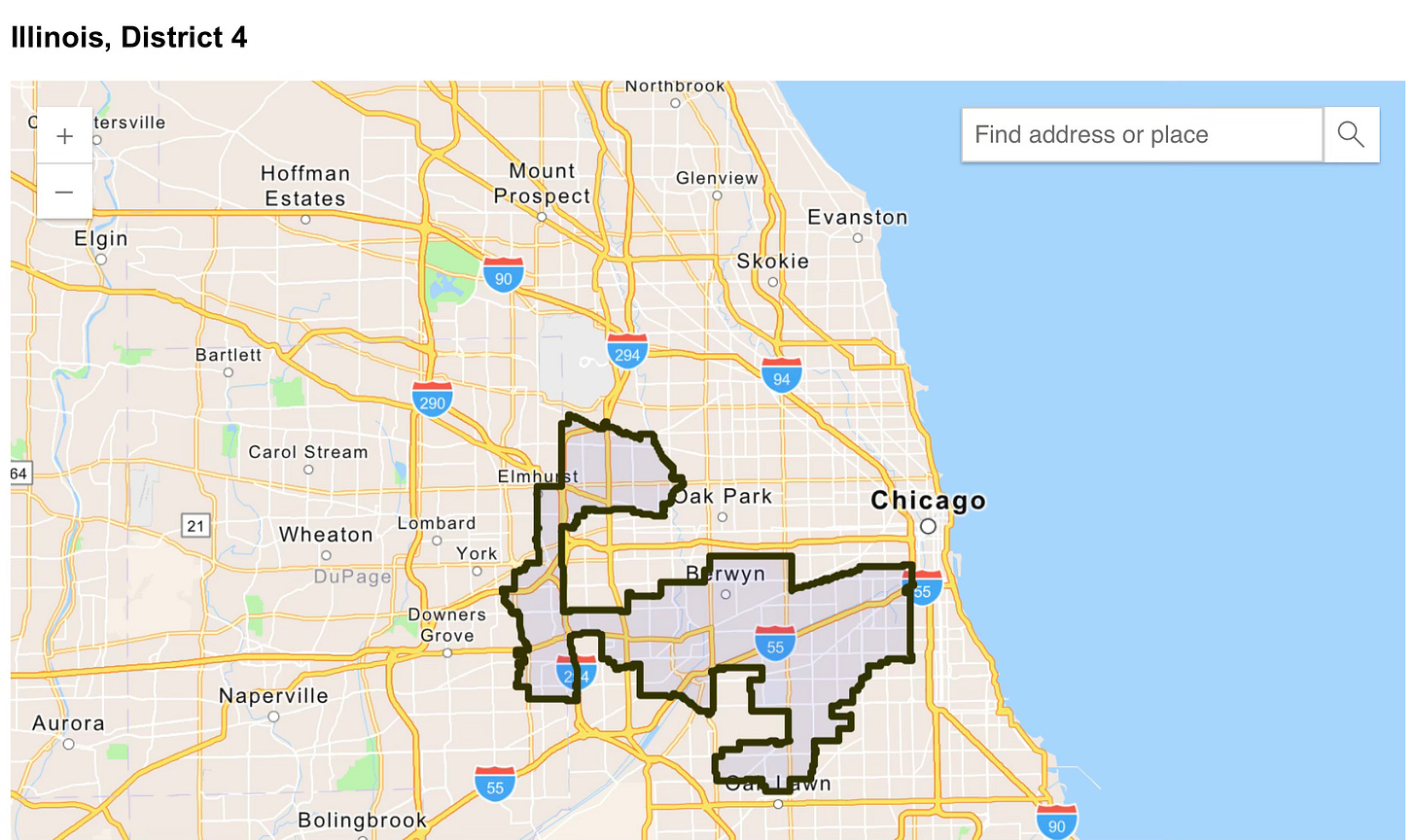

Another likely contributor to strict party line behavior is the state redistricting process where House members are ensconced in safe districts where allegiance to partisan legislation nearly guarantees reelection. Some maps that are drawn defy commonsense and logic. Neighborhoods can find themselves divided into separate congressional districts and lumped into unrelated neighborhoods in an effort to achieve a specific political balance. There are relatively few contested House seats where a single “wrong” vote can spell reelection defeat.

The consequences of the failure to adhere to a regular order law-making process may be best exemplified by Congressional budgeting and spending.

Since 1965, Congress has submitted only five balanced budgets. Those were for fiscal years 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2001. The last time the US enjoyed a budget surplus was in 2001. In the two-and-a-half decades since, the federal government begins the very first day of its fiscal year knowing it will spend more money than it takes in (e.g. taxes & tariffs).

It is difficult to imagine a candidate running for the House or Senate (or running for reelection to either chamber) on a platform of routinely spending more money than the nation has. Yet, hundreds of senators and congressmen and have voted for spending beyond the nation’s means without suffering serious consequences at the ballot box.

Predictably, they promise to enact responsible spending measures later. Later never arrives. For example, the budget blueprint offered by then-House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan in 2011 promised to eliminate the budget deficit. The opposing party labeled the plan “draconian.” Here’s the reality. Ten Olympic Games would come and go before the US government would spend less than it took in under the “Path to Prosperity” plan. Ryan’s measure was not serious. It was a gimmick that punted fiscal responsibility decades into the future.

Similarly, it’s been two decades since Congress passed all 12 appropriation measures as stand-alone bills. In fact, this has occurred only six times since 1990. The value of passing stand-alone appropriations bills is immeasurable. It is a transparent process that includes committee hearings, mark-ups, and committee reports. It provides the greatest opportunity for public scrutiny of the legislative process.

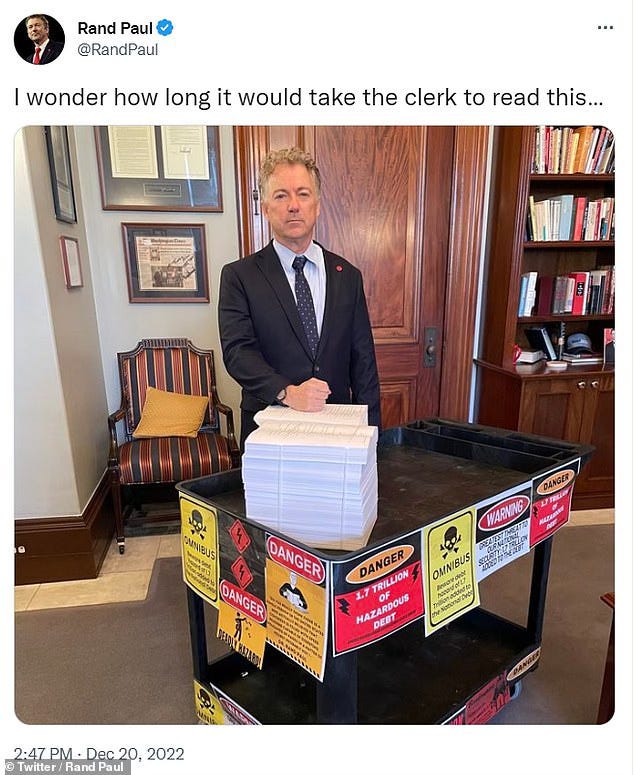

What has occurred with near absolute consistency in the last 25 years is the combining of all appropriations measures into a single, massive omnibus bill. Such a bill does not undergo the regular order law-making process. In most cases, the bill is crafted behind closed doors with only single party leadership involved.

To be more precise, this irregular order is completely party-centric with the majority party calling all the shots. Unlike the regular order of consideration of a bill in a committee, the minority party is not even in the room when an omnibus spending bill is drafted. Literally, not in the room. The rise of the giant, omnibus spending packages has also sidelined committee chairs, effectively removing them from the appropriations process.

Make no mistake, this refusal to pass all individual appropriations measures is a two-party issue. The failure to submit a balanced budget and the passage of stand-alone appropriation measures occurred when Democrats controlled both the White House and Congress, when Republicans were in charge, and when there was divided government.

No party has clean hands.

None of this has occurred in a vacuum. There are very few think tanks that cast a critical eye toward the federal government when it spends beyond its means. They sacrifice advocating for fiscal responsibility in return for Capitol Hill funding of their pet projects and favored programs.

The nation’s press has completely abandoned reporting on the budget and appropriations processes unless it’s to attack the political party they disfavor. Back in the days when I was a news commentator, I could count on one, two hands at most, the number of folks in the media who reported when Congress failed to pass a budget or stand-along spending measures. Today’s media truly doesn’t care.

Unfortunately, passing gigantic omnibus spending measures has become the new norm. Virtually the entire process is conducted in secret, hidden from public scrutiny, and without input from several hundred members of Congress of both parties.

The product of irregular order is spending measures, sometimes totaling more than 4,000 pages, that are jammed full of surprises. This approach of massive legislation crafted in secrecy was best described when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi infamously said in 2010 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, “We have to pass the bill so that you can find out what is in it.”

Mark Hyman is a 35-year military veteran and an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter (X) at @markhyman.

Mark welcomes all news tips and story ideas in the strictest of confidence. You can reach him at markhyman.tv (at) gmail.com.