(This essay is adapted from Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation.)

This year is the 20th anniversary of the FBI falsely identifying biomedical researcher Steven Hatfill as the perpetrator of the 2001 anthrax letter attacks despite finding no motive, lacking any evidence, and facing airtight alibis. The FBI eventually took the unprecedented step of formally exonerating Hatfill, declaring him innocent of the anthrax crimes, and the federal government paid him a multi-million dollar settlement.

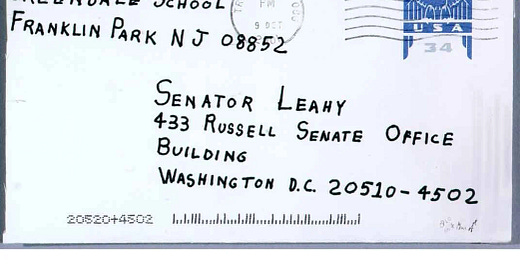

Shortly after the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, seventeen people became ill from the effects of the deadly bacteria, anthrax. Another five died. Three letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to public figures in Washington, DC, and New York City. Two of the fatalities were postal workers at a Washington, DC, mail facility. It is presumed they were exposed to anthrax contained in one or perhaps both of the two letters mailed to Democratic Senators Tom Daschle of South Dakota and Patrick Leahy of Vermont.

It is believed three other deaths were tied to whoever was behind the first two letters, but that has only been conjecture. An employee of the National Enquirer parent company was fatally stricken in Florida, a ninety-four-year-old woman in Connecticut died, and a Manhattan clerk perished from anthrax infection. No letters or other devices that carried anthrax spores were ever recovered in those deaths. About the same time, three hoax letters containing harmless powder were mailed from Florida to various recipients.

The nation was uneasy. The September 11th attacks were fresh on everyone’s mind. It was immediately presumed foreign agents from either al Qaeda or Iraq were responsible. There was intense pressure on federal investigators to apprehend a suspect or suspects.

Robert Mueller was the newly appointed director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the lead agency in the anthrax investigation. Mueller took over an FBI reeling from a very bad decade in the 1990s. The agency bungled several high-profile operations, sometimes at the cost of millions of dollars in settlements, and at other times resulting in the tragic loss of human life. Literally, thousands of lives.

An FBI sniper executed an improper shoot-to-kill order and fatally shot a woman holding a baby during the 1992 standoff at Ruby Ridge, Idaho. A Justice Department Office of Professional Responsibility investigation found FBI Special Agent Van Harp was embroiled in the illegal shoot-to-kill order coverup. A Justice Department investigator recommended Harp be disciplined. Instead, the FBI promoted him despite his key role in the coverup and the fact the US government paid a multimillion-dollar settlement over the tragedy.

The FBI took over from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms as the lead law enforcement agency in the 1993 siege of the Branch Davidians complex in Waco, Texas. The FBI operation ended disastrously, causing the fiery deaths of seventy-six worshippers, including twenty children.

The FBI was caught completely unaware when immigrant Islamic jihadists, encouraged by a prominent US-based radical sheikh, carried out the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Only good fortune prevented the North Tower from toppling into the South Tower. Still, six people died and more than one thousand were injured.

The FBI fingered security guard Richard Jewell as the 1996 Olympic Park bomber. Jewell was initially hailed as a hero for discovering a pipe bomb before it exploded. The bomb detonated before everyone at the park could be safely evacuated. One person was killed and more than one hundred were injured. In spite of his heroics, the FBI insisted Jewell was the bomber.

Acting on FBI leaks, several news organizations defamed Jewell. Months later, the FBI cleared Jewell, and the real perpetrator was eventually caught. Jewell received financial settlements from several news outlets for defaming him.

In 1999, the FBI accused US scientist Wen Ho Lee of stealing nuclear secrets and passing them to China. He was jailed in solitary confinement for nearly a year while the FBI attempted to build a case against him. No criminal case could be made against Lee and he was released from imprisonment with an apology. The US government paid him a seven-figure settlement.

For two decades, the FBI allowed informant Whitey Bulger to continue his crime spree. His criminal activity included countless murders. The agency let the Irish mobster and his crime family do as they please in return for tips on the Italian mafia. Bulger only passed on worthless information. FBI Special Agents John Connolly and John Morris were accomplices to Bulger’s criminal activity, including murder. The FBI complicity with Bulger became public in 1997.

The FBI involvement with Bulger was so corrupt that the agency permitted the murder convictions of four innocent men, Peter Limone, Joe Salvati, Henry Tameleo, and Louis Greco, by allowing a witness to lie, and by withholding exculpatory evidence in order to protect another informant and Bulger criminal accomplice.

Three of the four men were given death sentences. The fourth was given a life sentence. The sentences of the men on death row were later changed to life imprisonment. In the 1980s, the acting US Attorney for the Massachusetts District pressured the Massachusetts Parole Board to keep the framed men imprisoned. That person was Robert Mueller, who would become the FBI Director two decades later.

The four innocent men were eventually exonerated after serving more than three decades in prison, after secret FBI files revealed the bureau’s corruption. The men were paid a settlement of nearly $102 million, although only two received the money directly, since Tameleo and Greco died in prison. The level of Mueller’s knowledge of and involvement in the FBI and Whitey Bulger corruption scheme has never been fully explained. In 2007, while serving as FBI Director, Mueller dismissed the matter commenting, "I think the public should recognize that what happened, happened years ago."

Then there was the granddaddy of them all. The FBI and the federal intelligence community were asleep at the switch as twenty Muslim immigrants took flight lessons in order to fly jumbo jets into buildings during the 2001 terror attacks. Nearly 3,000 people died on September 11, 2001.

All of this tremendous baggage meant the FBI desperately needed a big win in order to restore public trust in the agency. It was now faced with that opportunity as long as it could solve who was behind the fall 2001 anthrax attacks. Disgraced FBI Special Agent Van Harp, of Ruby Ridge coverup infamy, was placed in charge of the investigation.

Progress was slow going, even though more than one thousand agents combed leads. The agency was under tremendous pressure from Senators Daschle and Leahy. Then, scientist Barbara Rosenberg began piecing together a profile of the type of individual she thought might be responsible, hinting it was a government employee who worked in biomedical research. Rosenberg began posting her analysis on the internet and some in the media weighed in, bringing attention to her theory.

Three months after the anthrax letters appeared, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof penned a column titled, “Profile of a Killer.” Kristof described the perpetrator as an American working in one of the military’s biological weapons program.

In a few months’ time, Kristof began taunting the FBI in column after column for its failure to find the anthrax killer. The “anthrax killer remain[s] at large” and could wreak panic by “send[ing] out 100 anthrax letters,” Kristof wrote. He added, the “failure to capture the anthrax killer [is] suggesting to Iraq and other potential perpetrators that they might get away with an attack” and it was time “to light a fire under the FBI.”

Kristof began making references to an unnamed American who worked at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Maryland, as the likely culprit. Kristof later admitted the FBI was feeding him information on the investigation.

While the FBI was funneling sensitive investigation details to Kristof, the columnist was using this inside knowledge to bash the agency for “bumbling,” “lackadaisical ineptitude,” “lethargy,” and “plodding in slow motion.” Kristof identified an individual who federal investigators would later call a “person of interest.” Kristof merely referred to him as “Mr. Z.” Kristof would continue to mock the FBI for being “unbelievably lethargic in its investigation,” while suggesting his Mr. Z was also involved in anthrax hoaxes in the 1990s.

The constant criticism by the New York Times may have spurred the FBI to take public action. FBI agent Harp despised coming under outside pressure. The FBI asked and received permission in June 2002 to search the Fort Detrick-area apartment of Steven Hatfill, a medical doctor who once worked at the Army medical research facility. Nothing was found. After a month of weathering heavy criticism, the FBI returned for another search. This time agents were armed with a search warrant and had a live-television-news crews in tow.

The FBI had previously been quietly talking to Hatfill, who had been very open and cooperative. However, that discreet investigation came to an end and the FBI turned its investigation of Hatfill into a full-fledged media circus. There were as many as two- to three-dozen persons of interest, but the FBI decided to make Hatfill’s investigation a public relations spectacle. Somebody, presumably inside the FBI, tipped off the media.

The FBI employed a scorched-earth policy toward Hatfill. He was fired by his government contractor. The teaching position he lined up at Louisiana State University ended the day it was to begin, after the FBI pressured the university to cancel his employment.

Agents began openly questioning family, friends, acquaintances, and coworkers. Hatfill’s picture was flashed to the locals in Princeton, New Jersey, where it was believed the two known anthrax letters were mailed. He was brazenly tailed by FBI agents like paparazzi chasing a celebrity. On one occasion, an FBI agent drove over Hatfill’s foot with a sports utility vehicle. The driver was not charged, but a local police officer issued Hatfill a jaywalking ticket.

Hatfill escaped to his girlfriend’s condominium in northern Virginia in order to get some peace. In response, the FBI installed a camera on a post aimed at the condo. Agents were stationed out front. The harassment did not stop. One day, Hatfill was twice stopped for lane-change violations by two different police officers only minutes apart. It seemed every cop had his number. News organizations pondered when the killer was going to be jailed.

Hatfill was working on a novel about a bioterrorism attack. The only copy of the novel was on the computer the FBI confiscated from his home. Excerpts from the novel appeared in the press.

The FBI began leaking Hatfill’s personal medical records, a blatant HIPAA violation.[1] There were media reports that Hatfill took Cipro before the anthrax attacks. Cipro is an antibiotic often used to treat bacterial infections, as well as anthrax exposure. The news reports did not include the fact that Hatfill was prescribed Cipro by his doctor to treat an infection after sinus surgery. The FBI was leaking misleading and legally protected information to the media.

Media reports claimed Hatfill had access to anthrax at Fort Detrick. To the contrary, Hatfill did not have access to the highly secure facility where contagious bacteria such as anthrax were stored. Hatfill was a virologist and worked in a completely different section of biomedical research.

Hatfill had previously visited a friend at his rural home in northern Virginia. The New York Times misleadingly called it a “safe house.” The Times implied he was involved in a massive genocidal anthrax attack on thousands in Rhodesia, where he attended medical school. Actually, the Rhodesia anthrax was natural-borne from a diseased cattle herd.

An FBI consultant analyzed the two brief notes in the anthrax letters. One was fifteen words long, the other twenty-four words. He also looked at the hoax letters. Then he penned a 9,600-word article in Vanity Fair, in which he named Hatfill as the “suspect” behind the anthrax letters.[2]

The FBI leaked to the press that it flew in from California three dog-handlers and three bloodhounds when agents first searched Hatfill’s apartment. The dogs supposedly “hit” on Hatfill. What was not reported in the press was the two major bloodhound organizations, the Law Enforcement Bloodhound Association and the National Police Bloodhound Association, reported those handlers and their hounds as being unreliable for criminal investigations.

There was not one scintilla of physical evidence tying Hatfill to the anthrax attacks. He had ironclad alibis for the times the letters were mailed. He voluntarily took and passed a polygraph test. The FBI could not produce one plausible motive for Hatfill to carry out the attacks. Yet, the law-enforcement agency persisted in pointing the finger at the scientist as the likely culprit.

The FBI’s orchestrated leaks of half-truths and misinformation may have been intended to force Hatfill to crack. FBI agent Harp admitted he had personally leaked information to at least a dozen journalists. Hatfill had become so hated by the public that he stopped leaving his girlfriend’s condo. He remained indoors for weeks at a time, became depressed, and began drinking heavily. He later said suicide was never an option because it would have allowed the FBI to posthumously declare him guilty.

It was highly unprofessional and legally suspect that the FBI was leaking so much personal privacy information to so many media outlets. That this was occurring with regularity in such a high-profile investigation suggests it was being done at the direction of FBI Director Mueller. Observers have noted the pattern of leaks to favored news outlets occurred years later when Mueller served as the special prosecutor in the Russia investigation.

In late 2003, Hatfill finally sued the Justice Department, the FBI, and several news outlets. Hatfill’s ironclad alibis and the complete lack of evidence tying Hatfill to the anthrax letters forced the FBI to admit it had been harassing an innocent man.

The federal government took the rare step of formally exonerating Hatfill of involvement in the anthrax attacks and paid him a nearly $5-million settlement. Several news organizations also reached financial settlements with Hatfill.

Hatfill’s lawsuit against the New York Times was eventually dismissed. The courts ruled Hatfill had a higher burden to prove the newspaper acted maliciously because he was a “public figure.” The irony is Hatfill was completely anonymous and only became a public figure after the FBI, the New York Times, and others falsely accused him of mailing the anthrax letters.

After the FBI’s Hatfill investigation collapsed, the agency turned its attention to another Fort Detrick biomedical researcher, Bruce Ivins. The agency’s treatment of Ivins was nearly identical to its harassment of Hatfill. Ivins was searched, investigated, his wife and daughters were questioned, and he was publicly followed wherever he went. Once again, by leaking privacy information to the press, the FBI portrayed him as an imperfect man with character flaws. This meant Ivins was just like millions of other people.

Allegedly damning circumstantial evidence offered by the FBI suggesting Ivins was the anthrax letter culprit included the fact that he owned handguns. Yet, like the Hatfill case, the FBI did not uncover one credible piece of physical evidence tying Ivins to the letters.

Ivins descended into depression after a year of around-the-clock surveillance and harassment of his family. On July 29, 2008, Bruce Ivins took his own life. A week later, the FBI, without offering any evidence and motive, declared Ivins the sole source of the anthrax letters and the agency closed the case. The FBI finally got a win.

Several scientific experts claim the FBI lacked the evidence to reach the conclusion Ivins was the source of the anthrax letters. Ivins’s colleagues insist the FBI got the wrong man.

It is likely the anthrax killer is still walking free.

Mark Hyman is an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter, Gettr, and Parler at @markhyman, and on Truth Social at @markhyman81.

His books Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation and Pardongate: How Bill and Hillary Clinton and their Brothers Profited from Pardons are on sale now (here and here).

[1] The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) is a federal law to protect sensitive patient health. Revealing such information without the patient’s consent is a criminal violation.

[2] Don Foster, “The Message in the Anthrax,” Vanity Fair, October 2003, 180-200.