“[F]ar too often you see Pentagon leaders making decisions based on talking points rather than actual hard concrete evidence.” Dan Grazier, Project on Government Oversight

Completely restructuring the Navy’s ship acquisition program should be among the highest priorities of the new administration. Every shipbuilding program is hopelessly behind schedule, in some cases by years. Too many ships in the fleet have been extended beyond their expected lifespans. And there is an acute shortage of needed ships. When a replenishment oiler ran aground in September it left the USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) battle group serving in the North Arabian Sea without an ability to refuel at sea. The Navy didn’t have a spare oiler to replace it.

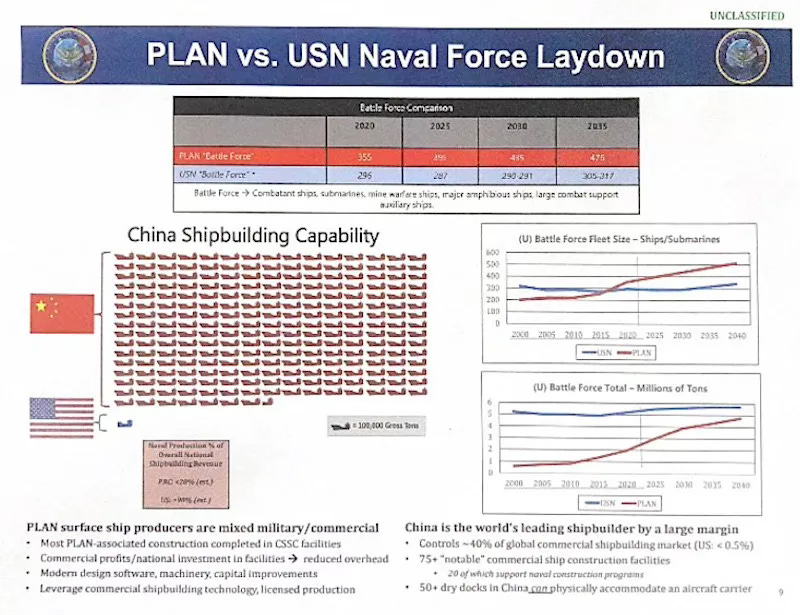

Making matters worse, global threats are increasing. Today, China has the world’s largest Navy and it’s getting bigger. According to a leaked Office of Naval Intelligence briefing slide, the Chinese navy has a shipbuilding capacity that is 200 times larger than that of the US Navy.

The Navy’s shipbuilding failures isn’t a recent problem. It has been building for years. Decades, actually.

The days of appropriate attention focused on all Pentagon acquisition programs has virtually evaporated. The Navy’s difficulties are mirrored among all the services. Defense Department acquisitions have been out-of-sight out-of mind by everyone outside of military circles.

Few in Washington, DC from the White House to Capitol Hill appear to care, which is odd considering the mindset to frequently deploy servicemen and women to every corner of the globe, including those that have very little impact on the US.

The Navy’s acquisition of the littoral class ship, or LCS, is representative of the problems facing that service. Just weeks after the 9/11 attacks, the Navy announced this new class of warship. The LCS was hailed as a transformational, 21st century platform to meet future defense challenges. But just a few years after production got into full-swing the Navy began mothballing the ships.

The LCS was promised to last a generation. Yet, some of the ships, such as the USS Sioux City (LCS-11), were decommissioned decades early. The Sioux City had completed a little more than 4 years of service, rather than the expected 25-years.

“The Littoral Combat Ship … was doomed from the beginning. It's because it was a flawed concept,” according to Dan Grazier. A Marine Corps veteran, Grazier is the senior defense policy fellow at the Project on Government Oversight. He’s been tracking the LCS program. Grazier was not alone in his doubts about the ship.

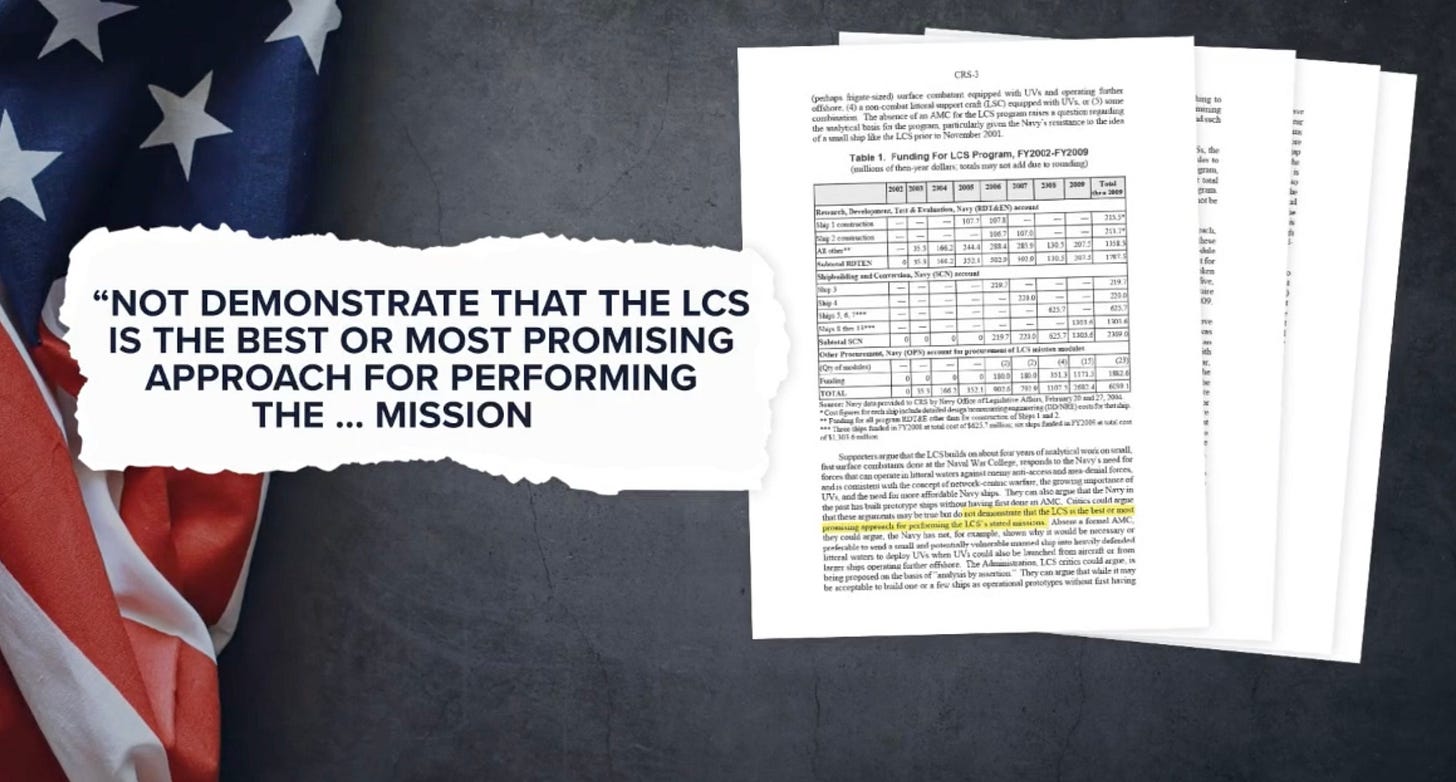

Several government agencies raised red flags before the first ship in the class (LCS-1 commissioned in November 2008) was even built. In the 2004, the Congressional Research Service warned the Navy did “not demonstrate that the LCS is the best or most promising approach for performing the … missions.”

The House Armed Services Committee expressed “concerns about the lack of a rigorous analysis of alternative concepts for performance of the LCS mission.” The following year, the Congressional Budget Office suggested Congress cancel the program and spend dollars elsewhere.

Operation Test and Evaluation, the Pentagon’s test and evaluation agency gave the LCS poor grades in a 2009 report. And the Government Accountability Office issued a 2010 paper stating “[T]he Navy’s ability to deliver a capable, affordable LCS remains unproven.”

Despite the overwhelming number of warnings, the Navy launched an aggressive plan to acquire more than 50 of the LCS class of ships. This plan to fail-forward may be due to the expectations of the Navy’s acquisition process. “Urging caution or raising an alarm regarding an acquisition is the fastest way to end a career,” a Navy official explained. This official spoke with us on the condition of anonymity due to their position. This expectation influences the senior officers involved in acquisition. The official continued, “The expectation of the Navy’s [seven program executive offices] is to keep an acquisition moving along, get a good [fitness report], get promoted and transfer to the next assignment. By the time problems emerge, they will be long gone and safe from accountability.”

Grazier suggested facts often take a back seat to the expected narrative. “Well, unfortunately, far too often you see Pentagon leaders making decisions based on talking points rather than actual hard concrete evidence.”

Most of the Pentagon and fleet officials we spoke with applauded the Navy’s effort to be forward-thinking and pursue cutting-edge technology, promised by the littoral combat ship. But the failure to consider competing concepts, conduct a detailed independent cost estimate, and skip operational testing that is critical in new ship construction proved catastrophic.

Rather than pick a single winner among three competing designs as is the common practice, the Navy awarded contracts for two different ships in 2004. This made Congressional delegations happy in Wisconsin and Alabama, locations of the winning shipyards. The two versions of the LCS were built at Lockheed Martin’s Fincantieri Marinette Marine Corporation in Marinette, Wisconsin and Austal USA in Mobile, Alabama.

Construction of the LCS quickly went downhill from the beginning. At $584 million, each LCS costs about two-and-a-half times the original estimate of $220 million per ship. Operating expenses skyrocketed. A novel concept to combine diesel and gas turbine propulsion systems to reach a high speed of 45 knots failed. In 2016, 6 of the first 7 ships built were out-of-commission due to mechanical failures (here, here, here, here, here, here).

The decision to assign skeletal manning left the ships short-staffed to perform basic duties, over-working the crews. Warships are not made of aluminum because it doesn’t withstand attacks. Yet, the Navy used aluminum in the LCS to lower its weight sacrificing survivability of the ship and crew. The Navy was willing to put sailors’ lives at risk.

Several of the ships developed structural cracks, reducing their seaworthiness. The plan to rapidly swap weapons systems modules in a Legos-like concept so the ships could change war-fighting tasks never reliably materialized.

Instead of a small, Jack-of-all-trades warship, the LCS has become the Navy’s version of the Yugo. The LCS is a combatant that punches well below its weight. By design, the LCS platform is exactly the type of combatant that should be deployed to counter the Houthis threat in the Red Sea. However, the Navy won’t send the ships because they are deemed ineffective and vulnerable to the Houthis’s third world military capabilities.

In 2012 as failures mounted, Navy’s Chief of Information Officer Rear Admiral John Kirby responded to critics stating, “[The] LCS is built to fight. It’s built for combat.” (Kirby was later appointed by President Joe Biden to serve as his chief Pentagon spokesman.) When problems became insurmountable and acknowledgement of the LCS failure was unavoidable, the Navy flipped. Last year, Vice Admiral Bill Galinis said, “[T]hey just don’t support the high-end fight that we’re getting ready for right now.”

Our detailed review of Navy documents reveals the lifetime cost to American taxpayers will be about $108 billion. The Navy declined to elaborate on cost totals nor answer any other questions. Instead, a Navy spokesman issued a statement that read, in part:

“In April 2020, the Navy established Task Force LCS with a mission to enhance the sustainability, reliability, and employability of Littoral Combat Ships. ... These efforts have improved the … operational availability of the LCS.”

In 2015, the Defense Secretary reduced the acquisition to just 40 ships. The total was further cut to 35. 32 have been commissioned, and 3 more are still under-construction (here, here, here).

In 2020, the Navy announced it would start retiring the LCS, long before their 25-year lifespan. Aside from the Navy’s official statements, it is difficult to find anyone who speaks favorably of the LCS.

Defense consultant Bryan McGrath observed, “Decommissioning them is a terrible decision. But the only decision worse than that would be keeping them.” Grazier added, “[F]uture historians are going to look back on it and they're probably going to shake their head like, why did the US Navy go down this road?”

Mark Hyman is a 35-year military veteran and an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter, Gettr, Parler, and Mastodon.world at @markhyman, and on Truth Social at @markhyman81.

His books Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation and Pardongate: How Bill and Hillary Clinton and their Brothers Profited from Pardons are on sale now (here and here).

I remember flying into San Diego in the 80s — the piers of the 32nd Street Naval Station bristling with masts, a result of John Lehman’s 600 ship Navy. Today it looks like a ghost town. Sad state of affairs.