“You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.” Attributed to Daniel Patrick Moynihan

This column does not excuse or defend the February 2022 Russia invasion of Ukraine. Rather, it addresses just one question: Did NATO promise not to expand toward Russia? Letters, State Department communiqués, meeting minutes and summit notes from during the last days of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact and recently made publicly available have revealed what was actually promised by the west — including the US — in the 1990s.

In discussing reasons for the invasion, President Vladimir Putin claimed a promise was made about 35 years ago that NATO would not expand its borders toward Russia. But that promise never happened, others claim. They insist no assurance was ever made to not move NATO closer to the Russian border. Besides, why did Russia believe it had any authority to make demands in the closing months of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, they ask.

The list of those who claim no promise was made that there wouldn’t be a NATO expansion eastward toward Russia is lengthy. Here are just a few.

Michael McFaul was the US ambassador to Russia (2012-2014) during the Obama Administration. By his own admission, US relations with the Russian people completely collapsed during his tenure. McFaul claims 60 percent of Russians had a favorable view of the US about the time he began serving in Moscow. When he departed his ambassador post, 83 percent of Russians had a negative view of the US. A three-year swing of 60% positive to 83% negative is mind-boggling. This is what’s referred to as a very, very bad report card on Obama diplomacy.

In a 2016 interview, the following was posed to McFaul: “[The] West has broken its promise that NATO would not expand into the East. How would you comment?” McFaul replied, “This assertion is a complete myth.” There was not promise, McFaul insisted.

McFaul was not alone in claiming no promise was made. Warren Christopher, who served as Clinton’s Secretary of State (1993-1997), may have thought it safe to lie in his memoirs published in 1998 that there was never a discussion with the Russians to not expand NATO. What Christopher did not live to see was the release of government records and papers, including several documenting his very own statements, that revealed the Clinton Administration misled Russian President Boris Yeltsin while quietly scheming to enlarge the organization with east European states. Clinton’s planned expansion did not include Russia.

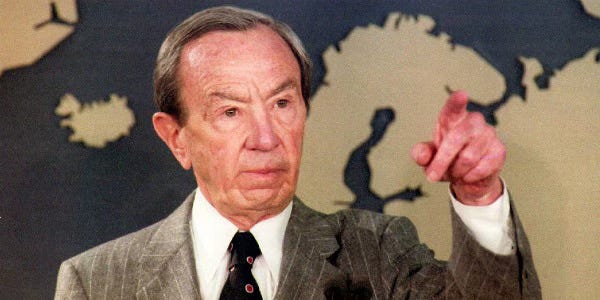

The 2022 claim by Robert Zoellick “there was no promise not to enlarge NATO” should be deeply embarrassing to Zoellick considering documents indicating otherwise had already been made public when he made his false claim. “I was in those meetings” during the last days of the USSR, Zoellick insisted. Undermining Zoellick’s claim was his boss, then-Secretary of State James Baker, III, made the first of many American promises to not move the NATO boundaries “one inch to the east.” Maybe Zoellick was thrown off because he never witnessed a pinky promise between Baker and Gorbachev.

Even if NATO did grow larger such expansion was a “comparatively smaller matter,” according to McFaul. This statement is ridiculous. Of course, it was not a small matter. In fact, it was a very big deal. NATO moving its lines closer toward the Russian border was and still is every bit as concerning to Moscow as was the deployment of Soviet missiles to Cuba in 1962 was to Washington, DC. The Kennedy Administration viewed Soviet military forces inching closer to the US as a military provocation. The US nearly went to war with the USSR over its increased military presence in Cuba. Even a deployment of Russian navy ships in international waters in the vicinity Florida just weeks ago led to some American hysteria.

Let’s review what actually happened 35 years ago.

First is the matter of Russia’s role in a post-Cold War Europe. Those who’ve argued that Russia had no say regarding what occurs on the European continent have no grasp of history. After the WWII defeat of Germany, the UK, US, USSR, and France concluded the Potsdam Agreement on August 1, 1945. The agreement gave equal power to each of the four victorious nations to determine the future of Germany. This equal power-sharing agreement would matter for half-a-century.

The cracks in America’s Cold War rival began to appear in the 1980s. President Ronald Reagan’s defense build-up probably did more to usher in the collapse of the Soviet empire than any other single event. To be fair, Mikhail Gorbachev’s domestic and national security policies helped hasten the end. Nonetheless, no one really anticipated how fast events would occur.

The first major breakthrough in the eastern alliance took place when West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev signed a joint declaration on June 13, 1989. This declaration affirmed the rights of peoples and states to self-determination. It was correctly viewed as Soviet acknowledgement that eastern Europe was moving away from Soviet satellite status.

Five months later, East German officials opened the gates to the Berlin Wall. The wall began to tumble down the following day on November 10, 1989 – literally – as citizens on both sides of the divide tore it down. The dissolution of the Warsaw Pact appeared imminent. It would end just months later in February 1990. Then on November 28, 1989, Kohl proposed a reunification of East and West Germany “if the people in Germany want it.”

In December 12, 1989 remarks anticipating dramatic changes in eastern Europe, US Secretary of State James Baker, III, expressed a goal to expand the role of NATO as a political organization “to build economic and political ties with the East.” Other NATO nations and partners were skeptical of what they viewed as a US powerplay. The French government did not agree with the US asserting itself into European matters. Neither did the British want to see the US be the dominant power in Europe going forward.

Kohl ended the year in dramatic fashion. In December 31, 1989 comments aimed at citizens of both East and West Germany, Kohl called for a reunification of both countries within the coming decade. Perhaps reunification would happen before the end of the century in about a decade’s time was the conventional wisdom.

On January 6, 1990, Kohl proposed NATO be replaced with a European security force, presumably one that would not include the US. His foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher delivered a major policy address on January 31st. Issues Genscher touched upon included relying on the Committee for Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) for political, security, and economic cooperation rather than other organizations (e.g. NATO). He also said that in order to calm Soviet concerns of possible military threats posed by a unified Germany NATO must rule out an “expansion of its territory towards the east, i.e. moving it closer to the Soviet borders.’”

Expanding the role the CSCE made sense to Genscher. The CSCE already included as members all nations of NATO, Warsaw Pact, and neutral nations: Austria, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland. Isolationist Albania was the only country in the European continent that was not a member.

A little more than a week later on February 9, 1990, a meeting was held in Moscow between Baker, Gorbachev, and Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze. The three discussed Germany reunification and other matters. Reunification between the two German nations was happening at a faster pace than anyone had anticipated. Baker assured the Soviets that in return for their support of a reunified Germany “there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east.”

It was at this meeting participants discussed what became known as “2+4.” These were the two Germanys, East and West, joined by the UK, US, USSR and France. Collectively, the six nations would decide the future of a unified Germany.

The USSR was keenly interested in this reconstituted Germany. Twice during the century, Germany launched major wars. The Soviets did not want to face a third major war launched from German soil. It did not want Germany to have a large standing army, the possession of nuclear weapons, or have NATO troops stationed in what had previously been East Germany.

During that meeting, Baker and Gorbachev were in agreement that a unified Germany operating within the structure of NATO would be more stable and less threatening to neighboring nations, including Russia. A neutral Germany may “decide that it needed its own independent nuclear capability as opposed to depending on the deterrent of the United States,” Baker told Gorbachev. The Soviet leader was in agreement telling Baker, “We don’t really want to see a replay of Versailles, where the Germans were able to arm themselves.” A rearmed Germany frightened the Soviets. Nearly 28 million Soviet military and civilians died during World War II.

Baker sent a letter to Kohl to apprise him of his conversations with Gorbachev, as Kohl was to meet with Gorbachev the following day. Baker wrote, “I put the following question to him, Would you prefer to see a unified Germany outside of NATO, independent and with no US forces or would you prefer a unified Germany to be tied to NATO, with assurances that NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position?” According to Baker, Gorbachev responded, “Certainly any extension of the zone of NATO would be unacceptable.”

The following day Gorbachev hosted Kohl in Moscow. Kohl emphasized Baker’s not “one inch to east” promise. Kohl told Gorbachev, “We believe that NATO should not expand its scope. … I correctly understand the security interests of the Soviet Union.”

Gorbachev outlined Soviet concerns “[T]he threat of war should not come from German soil; the post-war borders should be inviolable. …Germany’s territory should not be used by external forces [NATO].” Gorbachev assured Kohl that with military threats contained the USSR would support early reunification of the two Germanys.

In those early days of the east-west thaw, the Soviets proposed replacing the Warsaw Pact and NATO with the CSCE. The Soviets envisioned the 35-nation CSCE as the main organization to guide trade and ensure continent-wide security for years to come. The Soviets thought it made complete sense by focusing on CSCE and ending the two military pacts that defined the Cold War for decades.

Several months later the CSCE mechanism as the primary east-west organization was emphasized by Kohl in Moscow when he met quietly with Gorbachev in mid-July 1990. In discussions regarding a treaty between Germany and the USSR Kohl said, “The idea of a Soviet-German treaty will have a beneficial effect on other processes, particularly on establishing cooperation between NATO and the Warsaw Pact under the aegis of the OSCE.” The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe was the envisioned successor to CSCE.

During the meeting, Gorbachev agreed a unified Germany would remain a member of NATO, which Gorbachev believed offered to stability to whatever Germany emerged from reunification. It was Gorbachev’s understanding the military element of NATO would be deemphasized, the political aspect elevated, and like the Warsaw Pact, would fall under the umbrella of the OSCE.

The announcement of an agreement on German reunification by Gorbachev and Kohl shocked the world. The pair delivered the news in the small Russian town of Zheleznovodsk. US officials were caught off guard. They were not invited to nor were even given advanced notice of the talks. They learned of the agreement through press announcements. The US wanted to lead reunification talks. Instead, Germany and the Soviet Union took the initiative, creating angst in Washington, DC. The US wanted a leading role in determining the future of Europe.

Meanwhile, efforts to reduce military threats were already well underway. The 23 nations that were collectively members of the Warsaw Pact and NATO were furiously negotiating a new arms reduction treaty. It would eventually become known as the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty. By slashing armament totals through CFE inspection and destruction protocols, European nations believed they were reducing military threats and stabilizing the region. The treaty was finalized on November 19, 1990.

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany negotiated by the 2+4 powers was finalized earlier on September 12, 1990. Addressing Soviet worries over NATO moving closer to the USSR borders, the treaty stipulated no foreign troops would be stationed in what was formerly the East Germany. It stated “armed forces of other states will not stationed in that territory or carry out any other military activity there.”

About this time in late 1990, Poland and Czechoslovakia were becoming increasingly vocal about joining NATO after the Warsaw Pact formally dissolves. That prospect worried US ambassador to NATO William Taft. In both his private communications with President George HW Bush and in public statements Taft observed Gorbachev was deeply concerned about attempts to divide Europe when prospects of European integration were high. Taft said, “We ought to reach out to these countries [Poland, Czechoslovakia] to make sure that they understand and the Soviet Union … understands we are not indifferent to their security.” Taft continued, “That is about as much as we can do without re-dividing Europe and isolating the Soviet Union, which would be a very serious mistake.”

Major events continued throughout 1991. On February 25, the Warsaw Pact declared an end to the organization. On July 10, Boris Yeltsin was inaugurated as president of Russia, which was still a member-state of the Soviet Union. Then on December 25, the USSR formally dissolved and Mikhail Gorbachev left his office.

Russian President Boris Yeltsin sent a letter to NATO’s North Atlantic Cooperation Council on December 20, 1991. But before delivering the letter, the Soviet ambassador to Belgium, who was representing Russia at the NACC meeting, stunned the gathering by announcing that at that very moment the USSR ceased to exist. Then the ambassador revealed the contents of Yeltsin’s letter. Yeltsin expressed Russian interest in NATO membership. He wrote, “Today we are raising a question of Russia's membership in NATO, however regarding it as a long-term political aim.”

By 1992, discussions regarding NATO expansion were paused due to uncertainty as to who would be elected president in November, and while the break-up of Yugoslavia was capturing world attention. Fighting broke-out taking thousands of lives.

NATO had become a massive bureaucracy during its four decade life-span and was looking for relevance in the post-Cold War era. It became preoccupied with Yugoslavia and offered to assist UN peace keeping forces to patrol some of the former provinces of Yugoslavia. Then NATO abruptly changed its Yugoslavia mission to sanctions enforcement.

By September 1993, the drive to expand NATO by adding specific east European states began to heat-up. Yeltsin raised fresh concerns about drawing another dividing line through Europe. In a letter, Yeltsin expressed Russian opposition to Poland and the Czech Republic joining NATO unless Russia could simultaneously join. Yeltsin believed moving NATO’s boundaries closer to Russia without including Russia in the military pact undermined European security. A Russian Foreign Ministry official was adamant, “Europe must be indivisible.”

On October 20, 1993, a State Department official told the press that at a National Security Council meeting President Bill Clinton decided the US would support NATO expansion to include Russia and former states of the Warsaw Pact. This was a reversal from the US position four months earlier in June when Secretary of State Christopher told NATO foreign ministers in Athens that NATO expansion was not being considered.

NATO officials had been struggling with redefining the organization’s mission now that its putative enemy was gone. NATO defense ministers had already signed-off on Russian military participation in NATO-led peacekeeping missions and training exercises.

Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev reiterated Russian desire to join the western alliance. “Expansion of NATO membership without our participation does not suit Russia even if this is not aimed against us,” said Kozyrev.

Christopher traveled to Moscow to meet with Russia’s Yeltsin on October 22, 1993. It was at this meeting Christopher misled Yeltsin regarding the future of Russia as a member of NATO. Christopher told Yeltsin that Clinton saw Russia as integral fixture in Europe’s future. “There could be no recommendation to ignore or exclude Russia from full participation in the future security of Europe,” Christopher said. He continued, “As a result of our study, a ‘Partnership for Peace’ would be recommend to the NATO summit which would be open to all member of the NACC [North Atlantic Cooperation Council] including all European and NIS [newly independent states] states. There would be no step taken at this time to push anyone ahead of others.” An excited Yeltsin replied, “This is a brilliant idea, it is a stroke of genius.”

The Partnership for Peace represented everything both Gorbachev and Yeltsin had been requesting: a new organization to supplant NATO, and to which every European nation could become a member. Christopher did not tell Yeltsin that PFP was intended to be subsidiary of sorts of NATO and PFP members were being scrutinized for possible membership – like an audition – in NATO.

Christopher engaged in identical misleading claims with Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev, before he spoke with Yeltsin. According to a State Department summary of the meeting “Kozyrev asked, pointedly, whether there would not be two or three new members [of NATO] now? Secretary Christopher said no, that we were emphasizing a Partnership for Peace [that] … would definitely be open to all and there would no predetermined new members.”

Christopher’s statements to Kozyrev and Yeltsin were misleading at best. At worst, lies. The Clinton administration was quietly working to admit Poland and Czech Republic as quickly as possible. A classified State Department document titled “A Strategy for NATO’s Transformation and Expansion” had been prepared six weeks earlier. It identified 10 European states including former Warsaw Pact members it would admit to NATO prior to Russian admission. Russia’s admission was targeted for more than a decade later in 2005.

Russia was suspicious of the promises made by Clinton and Christopher. It wouldn’t be the first time Russians felt they were betrayed by the United States. One of the greatest humiliations the Russians suffered in the 20th century occurred in the first years of the new century.

At the urging of US President Theodore Roosevelt, the Japanese launched a surprise attack on Port Arthur in early 1904. Located in the northern Yellow Sea, Port Arthur was a warm water naval base Russia leased from China. Japan had plans for regional domination, and it viewed Russia as an obstacle in its goal to expand into Manchuria and the Korean peninsula. Japan reasoned it needed to take Port Arthur to further its expansionist aims.

The Russian navy was superior in size to Japan’s fleet. However, Japan held its own and eventually won the war with a shock victory at the battle of Tsushima in May 1905. The peace accord, negotiated in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in the autumn 1905, became known as the Treaty of Portsmouth. It was mediated by Roosevelt, for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Russians lost a war to Japan that was encouraged by Theodore Roosevelt, who negotiated the peace treaty, in his own country, and received the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. It was a deep humiliation for Russia at the hands of Roosevelt and the Americans.

In late 1993 just a year after stepping down as Secretary of State, James Baker addressed his concerns in an opinion column of including eastern European nations in NATO, but excluding former members of the Soviet Union. Bake had been reading the Clinton Administration tea leaves regarding NATO expansion. “Such an ill-advised approach would not only sow the seeds of revanchism and a revived Russian empire, it would also undermine the independence of the 11 non-Russian independent states of the former Soviet Union. Perversely, it could prompt some states of Central Asia and the Caucuses to look south to places like Tehran for security.” Baker urged Russia membership in NATO as a goal toward achieving stability. Its membership would “mark a milestone on the road to full integration with the West.”

It was clear the Russians were concerned. Clinton attempted to calm their worries. At the January 1994 NATO summit, Clinton told attendees efforts should be focused on Partnership for Peace and not NATO expansion as “it does not draw another line dividing Europe a few hundred miles east.”

Russians were understandably suspicious when Clinton insisted NATO expansion would not occur anytime soon. Clinton’s diplomatic envoys were simultaneously urging eastern European states to join the Partnership for Peace. Yeltsin correctly interpreted PFP as a fast-track attempt for certain east European states to join NATO, and not as a separate group to replace NATO and the Warsaw Pact, as he was previously led to believe by Christopher.

In a June 1994 letter to Clinton, Yeltsin reiterated Russia’s desire to join the G-7 and to expand the CSCE to supplant the European Union, the Council of Europe, NATO and other smaller groups. Yeltsin proposed an expanded CSCE could work toward controlling drug trafficking, money laundering, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, among other goals. Further, Yeltsin even urged participation in the organization by Japan.

At their September 1994 summit, according to the White House notetaker, Clinton assured Yeltsin that Russian membership in NATO was on the table. “I never said we shouldn’t consider Russia for membership or a special relationship with NATO. So, when we talk about NATO expanding, we’re emphasizing inclusion, not exclusion.” Clinton continued, “NATO expansion is not anti-Russian; it’s not intended to be exclusive of Russia and there is no imminent timetable.”

Except there was a timetable. The Clinton administration was working behind-the-scenes toward NATO membership by Poland and the Czech Republic. The Russians were suspicious the US was keeping Russia in the dark about actual NATO expansions efforts. In an early December 1994 letter, Yeltsin expressed concern because efforts by Clinton to expedite admission into NATO by mid-1995 of some central and east European states “will be interpreted and not only in Russia as the beginning of a new split of Europe.”

In his December 12, 1994 reply letter to Yeltsin, Clinton wrote “the most important strategic aim of the U.S. is to help construct a unified, stable and peaceful Europe in the next century in which Russia, the United States and all countries of Europe can fully participate. … This process must result in Russia’s full integration with the west through your future participation in GATT and the World Trade Organization, the Paris Club and … the closest collaboration between Russia and NATO.”

In a follow-up letter later that month Clinton conveyed “my strong commitment both to the U.S.-Russia partnership and to the goal of a stable, integrated and undivided Europe.” Clinton added, “we should discuss how to deepen Russia’s relationship with NATO.”

In one-on-one discussions, US diplomats were assuring the Russians there would be no expansion of NATO before the end of the century. This was very important to Yeltsin as he had domestic political disturbances to quell. After 80 years of socialist rule, Yeltsin and his allies were trying to shore up support for closer integration with the west while simultaneously holding at bay former Soviet hardliners who were suspicious of US intentions and were worried Yeltsin would capitulate, leaving Russia vulnerable to the west.

In December 1994, Zbigniew Brzezinski, who was National Security Adviser to President Jimmy Carter, proved prescient when he warned Clinton against expanding NATO without “a strategic vision.” Brzezinksi wrote that expanding NATO without including Russia would leave it “excluded and rejected, they will be resentful, and their own political self-determination will become more anti-European and anti-Western.”

In their Moscow meeting in May 1995, Yeltsin told Clinton “For me to agree to the borders of NATO expanding towards those of Russia – that would constitute a betrayal on my part of the Russian people.”

In July 1997, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland were formally invited to join NATO. They joined the treaty organization on March 12, 1999.

The promises not to expand NATO eastward made by Germany and the George HW Bush and Bill Clinton administrations were never honored.

Mark Hyman is an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter, Gettr, and Parler at @markhyman, and on Truth Social at @markhyman81.

His books Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation and Pardongate: How Bill and Hillary Clinton and their Brothers Profited from Pardons are on sale now (here and here).

In my opinion, the EU & NATO have, in effect, become the Fourth Reich, gobbling up nation after nation in Europe.Their next prize? Russia. That's what they've always wanted.

Napoleon tried and failed to conquer Russia. A certain Bohemian corporal and his Third Reich tried and failed to conquer Russia. Both were ignominious defeats.

But the EU / NATO? The Fourth Reich? They won't fail. Not at all. THEY will succeed where Napoleon and that Bohemian corporal failed.

This is what it has been ever since the end of World War II. Of course, the Soviet Union and its socialism were not good. Stalin supported Mao Zedong in Mao's quest to conquer China. But underneath that veneer of Socialism in Russia was Christianity, the religion of Russia & the Russian people from almost the very beginning.

Once Russia kicked out Socialism and returned to its roots, the Socialists in Europe went into a rage and now are working yet again to impose Socialism onto Russia.

By the way, remember who sponsored Vladimir Lenin from Switzerland to Russia: Germany.

Germany wanted to disable Russia's participation in the "Great War" and that's precisely what happened when Lenin & his Bolshevik communists conquered Russia.

Today, though, the Fourth Reich may get a very nasty surprise.

Thank you. This was both stomach-churning and heart-breaking to read.