“The Senator from the South Carolina has read many books on chivalry and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course, he has chosen a mistress to whom has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight: I mean the harlot, Slavery.” Charles Sumner speaking on the Senate floor, May 19, 1956

Charles Sumner was a US senator from Massachusetts. He was a member of the two-year-old Republican Party. Prior to becoming a Republican in 1855, he was a member of the Free Soil Party. He was also a harsh critic of the institution of slavery in the years leading up to the Civil War.

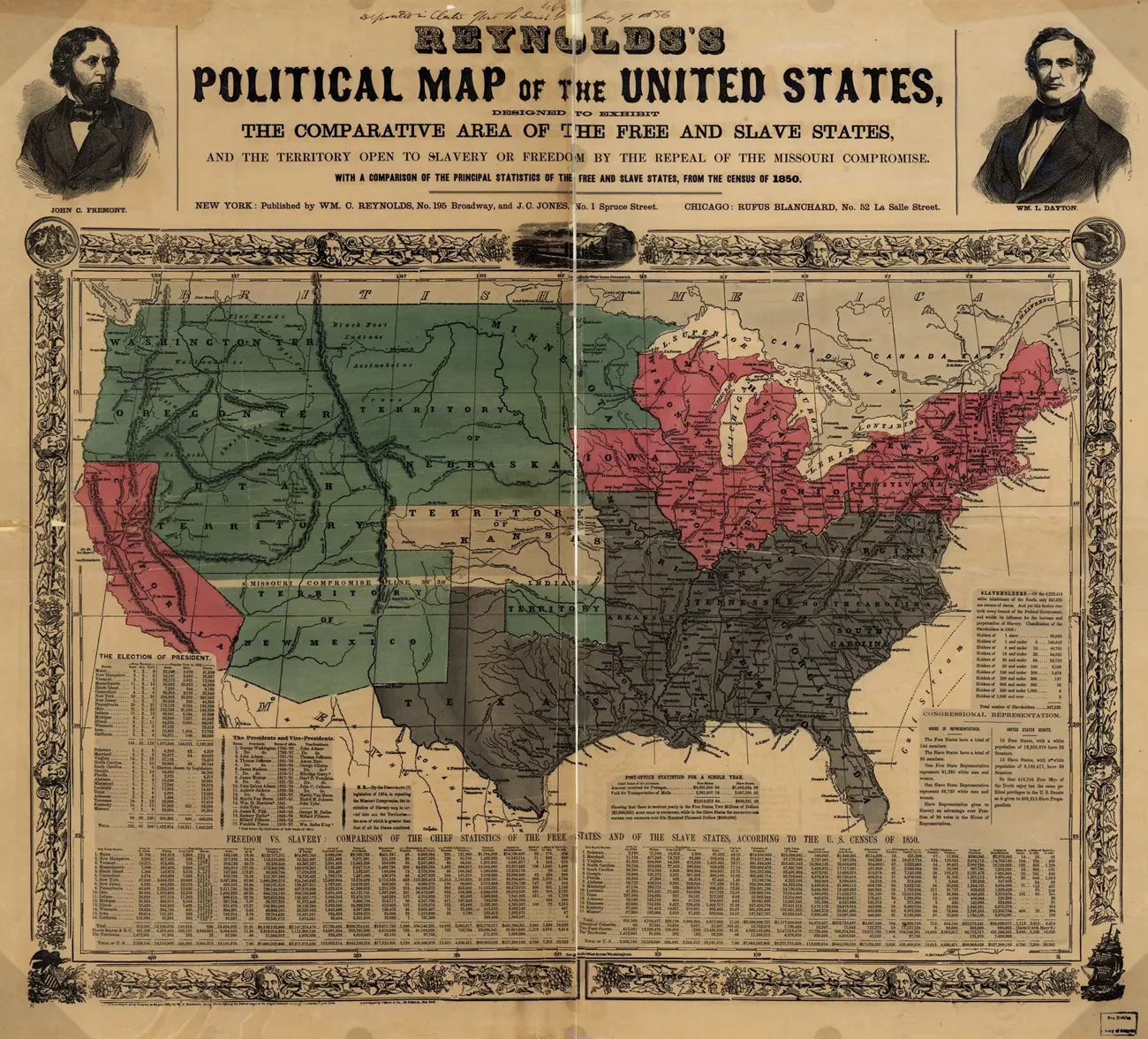

In spring 1856, debate was taking place in Congress regarding the Kansas territory. Should the territory be admitted to the Union? Under what preconditions? Would it be a slave state or a free state?

On May 19, 1856, Sumner rose to deliver a speech he titled “The Crime Against Kansas.” He would speak for three hours before the Senate adjourned. He continued his remarks for another two hours the following day.[1] Regarding the movement to admit Kansas as a slave state, he said, “It is the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State, hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of Slavery in the National Government.”[2]

Sumner’s criticism of the institution of slavery was incendiary to those who supported the practice. Then he directed his attention to those he believed were responsible. “I derive well-founded assurances of commensurate effort by the aroused masses of the country, determined not only to vindicate Right from Wrong, but to redeem the Republic from the thralldom of that Oligarchy which prompts, directs, and concentrates the distant Wrong.”[3]

Sumner singled out a pair of senators, who, he said, “have raised themselves to eminence on this floor in championship of human wrong: I mean the Senator of South Carolina [Mr. Butler] and the Senator from Illinois [Mr. Douglas] who, though unlike as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, yet, like this couple, sally forth together in the same adventure.”[4]

Then he turned his attention exclusively to Butler: “The Senator from the South Carolina has read many books on chivalry and believes himself a chivalrous knight with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course, he has chosen a mistress to whom has made his vows, and who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight: I mean the harlot, Slavery.”[5]

Sumner wasn’t finished. He blasted President Franklin Pierce for lying about the circumstances surrounding the admission of Missouri as a slave state. The slaveholding states had not “reluctantly acquiesced” in accepting the Missouri Compromise as Pierce had suggested. Sumner quoted from a letter by South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney as claiming the Compromise “is considered here by the Slaveholding States as a great triumph.”[6]

Sumner’s remarks were considered so powerful among abolitionists that his speech was reprinted in newspapers in the United States and Europe. His speech was used as a campaign document in the 1856 presidential election. As many as one million pamphlets memorializing his remarks were distributed.[7]

Not all those present in the Senate chamber agreed with the tone and the message of Sumner’s remarks. Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas wondered if it were all a trap. “Is it his object to provoke some of us to kick him as we would a dog in the street, that he may get sympathy upon the just chastisement?”[8]

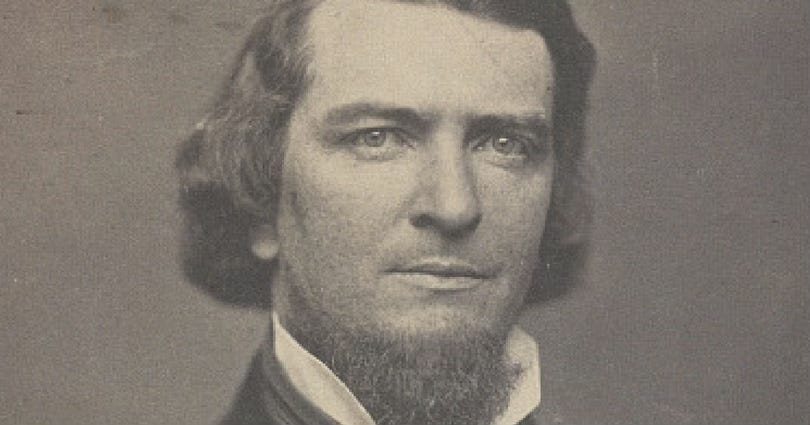

Preston Brooks was a South Carolina Democratic congressman. He was also a cousin of Butler. Brooks was in the Senate gallery the first day of Sumner’s speech. Brooks heard the Massachusetts senator liken his cousin to the Don Quixote of slavery. He waited until Sumner’s complete speech was published the following day. He became incensed after reading all of Sumner’s remarks and felt it was his duty to defend the honor of South Carolina and his cousin, whom he deemed was too elderly and frail to physically fight the Massachusetts senator.

Brooks thought that, under the circumstances, Southern code prevented him from using a pistol or sword to exact revenge. Some time earlier, Brooks had once joked that members of Congress should be required to check their firearms at the House cloakroom before entering the chamber. There would be no firearms use when he defended the honor of his cousin and the Palmetto State.

Brooks walked with a noticeable limp from a bum hip that was injured in a duel.[9] He used a walking cane to compensate for the limp. He settled upon the cane as a weapon to use against Sumner. After the Senate adjourned around midday on May 22, Brooks entered the Senate chamber in search of Sumner.

Brooks sat in the back as senators and other hangers-on gradually exited the chamber. Sumner was at his desk with pen in hand, writing furiously. Brooks approached Sumner’s desk. “Mr. Sumner,” Brooks said. “I have read your speech twice over very carefully. It is libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.” As Sumner started to rise from his desk to face his accuser, Brooks began striking him repeatedly with his gold-headed cane. Brooks struck Sumner at least thirty times by his own count, shattering the cane in the process.[10]

The attack was over in a matter of moments. Sumner lay covered in blood, unconscious, on the Senate floor. Others responding to the commotion had their own confrontation. Senator John Crittenden, a member of the Know-Nothing Party from Kentucky, approached Brooks as if to stop him. Democratic Representative Laurence Keitt of South Carolina implored Crittenden not to interfere and raised his own cane to emphasize his point. Democratic Georgia Senator Robert Toombs, who was near the fracas, did nothing to stop it. “I approved of it,” he later said of the assault.

Brooks was later arrested for assault. But his reputation had been made. He was a hero of the pro-slavery movement. Abolitionists were shocked over the attack. The nation was divided, with Northerners generally viewing Brooks as the perpetrator and Southerners considering Sumner the instigator.

Anticipating a vote of expulsion, Brooks resigned his House seat. However, his constituency viewed him as a hero for his actions and immediately elected him back into Congress.[11]

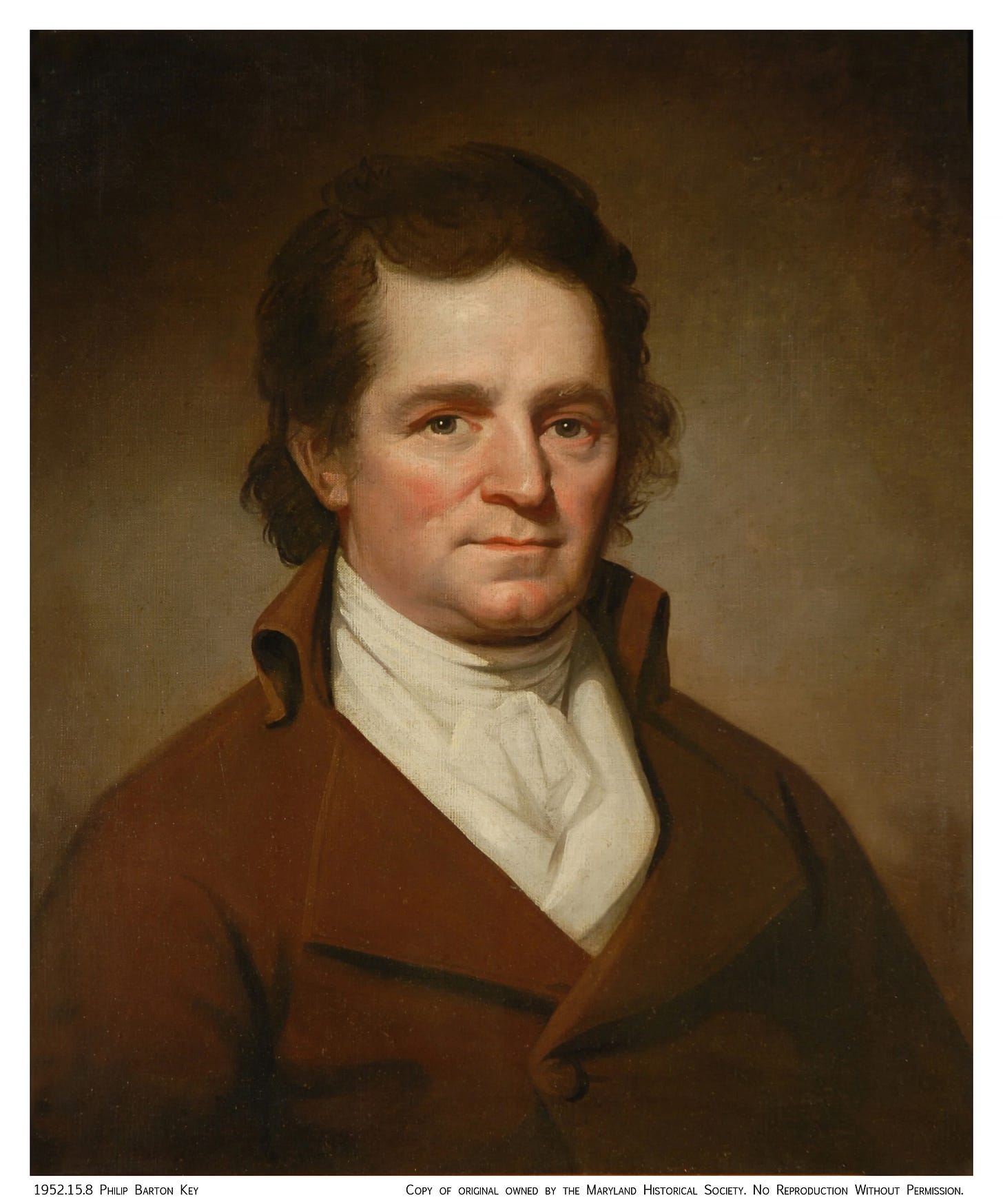

Brooks was tried in court on a charge of assault. In a bench ruling, Brooks was fined a paltry $300. Among the reasons for such a light sentence was the reported ineffectiveness of the prosecutor, Philip Barton Key, II. As the US attorney for Washington, DC, Key would find himself involved in more than one public scandal.[12]

Mark Hyman is a 35-year military veteran and an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter (X) at @markhyman.

Mark welcomes all news tips and story ideas in the strictest of confidence. You can reach him at markhyman.tv (at) gmail.com.

[1] Edward L. Pierce, Memoirs and Letters of Charles Sumner, (Boston:

Roberts Brothers, 1893), 448-449.

[2] The Works of Charles Sumner, Vol IV, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875),

140.

[3] Ibid, 143.

[4] Ibid,144.

[5] Ibid,144.

[6] Ibid, 144.

[7] David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Coming Civil War, (New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1961), 302.

[8] Ibid, 286-287.

[9] Williamjames Hull Hoffer, The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor,

Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War, (Baltimore: The Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2010), 7.

[10] David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Coming Civil War, (New York:

Alfred A. Knopf, 1961), 294-295.

[11] Archibald H. Grimke, Charles Sumner: The Scholar in Politics, (New

York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1892), 284-285.

[12] Williamjames Hull Hoffer, The Caning of Charles Sumner: Honor,

Idealism, and the Origins of the Civil War, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 2010), 80-81.