It’s the tenth anniversary of when Superstorm Sandy struck the Atlantic coast. In the political aftermath were a pair of federal appropriations measures that totaled more than $60 billion in spending. In a two-part series, I first examine the spending measures to include documenting how much actually constituted emergency spending, and how much went to actual storm relief. The second essay will scrutinize media organizations that claim to have fact-checked how that money was spent.

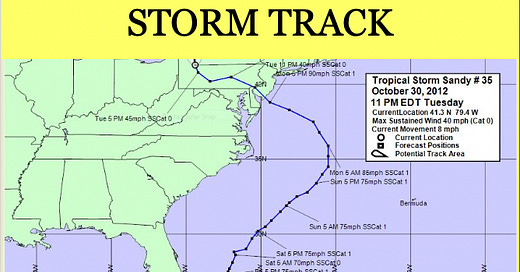

The Storm. In late October 2012, Sandy became the 18th named storm of the 2012 hurricane season. The weather event was a category 2 hurricane when it struck Cuba, but by the time it made landfall on the mid-Atlantic coast the National Weather Service downgraded Sandy to tropical storm status.

Despite the less powerful winds of a tropical storm, Sandy created a huge storm surge resulting in significant flooding in several coastal states, particularly New Jersey and New York. Oftentimes, flooding can be the most damaging of natural disasters.

The popular political and news narrative then and now was Superstorm Sandy “affected” as many as 24 states. But “affected” does not necessarily mean there was catastrophic or even significant storm damage. For example, “Sandy brought snow to the higher elevations from the Carolinas north into West Virginia and Maryland” is just that: early winter snow.

Twelve states and DC were declared disaster areas. These were: Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Sandy was a bureaucratic mess before the storm ever reached US shores. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has emergency provisions stockpiled around the nation to be immediately deployed when disaster strikes.

In the months leading up to Sandy, FEMA officials took the head-scratching move of removing from emergency stockpiles and selling hundreds of new or lightly-used residential trailers. Some of these were stockpiled in New York that could have housed some of the thousands left homeless from Sandy. According to a news investigation, trailers valued at $25,000 were, in some cases, sold for less than $4,000. And nearly a week passed after Sandy struck before FEMA even solicited bids for bottled water. That irresponsible delay is shocking since bottled water is the number one priority for disaster victims.

There was also mismanagement at the local level. New York City did not deploy dozens of pieces of emergency equipment including portable generators, tower lighting, and heaters, as well as bottled water and Mylar “space” blankets that were in critical need. The equipment was stashed in Central Park awaiting the New York City marathon.

Out-of-state utilities trucks that voluntarily arrived in New York after Sandy struck to help make repairs and restore power were chased out of the state because the workers were non-union. This happened despite the fact nearly a quarter of million New Yorkers living without electricity were told they may have to wait as long as two months before power would be restored.

Congress. One of the very first acts of the 113th Congress when it convened in January 2013 was to quickly pass H.R. 41. This bill granted the National Flood Insurance Program a raise in funding by nearly $10 billion from $20.725 billion to $30.425 billion to meet an anticipated increase in flood insurance claims.

Although there was generally widespread agreement in both chambers of Congress for the need to plus-up funds for the NFIP, some members were concerned there were no offsets to counter the increase in federal spending. Congress had increased the nation’s debt ceiling months earlier, and it had implemented legislative measures to limit spending. This plus-up upset the nation’s fiscal balance sheet.

Nonetheless, Congress was far from finished spending money.

A second bill with a final total of $50.4 billion, named the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act 2013, became the problem. First, consider the enormity of the spending. According to a Harvard Political Review paper, the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act was “larger than the entire budget of the Department of Homeland Security, bigger than the Department of Justice, and bigger than NASA, the Department of the Interior, and the International Assistance programs combined [emphasis added].”

According to Rep. Harold Rogers (R-KY-5), who introduced the bill, the “critical funding will go a long way toward repairing vital infrastructure, aiding troubled businesses, and getting victims back in their homes and back to work.” But there was a lot more spending in the bill than designated for making repairs.

The Spending. Bloated with a majority of the spending unrelated to Sandy, the Disaster Relief bill was enacted at a time when federal spending was to comply with the Budget Control Act of 2011.

The BCA set spending limits that could only be exceeded by emergency and disaster appropriations. The BCA also put in place sequestration that mandated nearly $110 billion in spending cuts in discretionary spending in the months leading up to the Disaster Relief bill.

President Barack Obama requested, and Congress considered, to designate all the appropriations as either disaster or emergency spending. Such a loophole would allow the bill to avoid mandatory budgetary offsets and it would bust through established spending limits. A cynic might conclude this financial sleight of hand would permit the disaster spending bill to serve as a political vehicle to restore some of the mandated spending cuts. Eventually, only about $3.5 billion of the bill was deemed to count against discretionary budget caps. The balance of the money was designated as either emergency or disaster relief spending despite the fact the majority of it was not.

Despite the legislative wordsmithing success when it came to the bookkeeping aspect of the act, Obama’s own Office of Management and Budget acknowledged that only $23.6 billion (39%) of the Disaster Relief appropriations requested by the president ($60.4 billion) were for immediate storm damage relief. The remaining $36.8 billion (61%) in spending was for unrelated acquisitions, upgrades, repairs, and mitigation of possible future storms. This nearly $37 billion in new federal spending should have been considered under the annual appropriations process, and not be falsely portrayed as emergency disaster relief, as the White House and Congress attempted.

Still, suggesting the nearly $37 billion in new spending should have been considered under the normal appropriations process is easier said than done. As I noted in an earlier essay (Irregular Order, September 11, 2022), both political parties long ago abandoned a century of Congressional history in its regular order of proposing, debating, amending and passing appropriations under the public’s watchful eye. Instead, Republicans and Democrats favor using large omnibus measures crafted behind closed doors, oftentimes to hide as many political handouts and pork barrel goodies as possible.

To underscore the pure politics of Congress’ profligate spending, 47 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were eligible to receive funds from the Disaster Relief bill. Remember, only 12 states and DC were declared disaster areas. The popular political and news narrative was 24 states were “affected.” But 49 jurisdictions were eligible to receive disaster-related appropriations. Only Arizona, Michigan, and South Carolina were left empty-handed. Even Alaska and Hawaii received money from a bill whose original premise was emergency spending to counter Sandy-related damage.

Eventually, Congress approved $10 billion less in spending than Obama requested. The final tally of the second spending measure was $50.4 billion. The $26.8 billion in non-emergency spending represented 53% of the total bill.

The Misuse. Some money that was ostensibly earmarked as Sandy-related was not. Here is just a sampling of the many examples. Chicago was given $63 million to upgrade city sewer and water systems. Obviously, the upgrades were not related to Sandy. Perhaps more importantly, why should federal taxpayers foot the bill for Chicago’s sewer upgrades when every other community must pay for their own?

Meanwhile, the town of Springfield, Massachusetts got nearly $22 million dollars to revitalize low-income neighborhoods. One might consider this a noble goal, but it is not Sandy-related nor is it an emergency.

Congress doled out money to countless pet projects and favored constituencies such as:

Millions (000,000) Program

$ 2 Smithsonian for pre-existing roof repairs*

$ 3 Grants to states for coastal studies

$ 10 FBI salaries & expenses

$ 15 NASA; $11M more than needed for repairs

$ 25 Weather forecasting improvements

$ 50 Mapping, charting and geodesy services

$ 50 Interior Dept Historic Preservation Fund

$ 88.3 Defense Department

$ 100 Head Start

$ 118 Amtrak**

$ 125 Colorado wildfire prevention

$ 150 Alaska fisheries

$ 348 National Park Service construction

$ 359 NOAA expenditures***

$ 2,000 Federal Highway Administration

$ 2,900 Army Corps of Engineers****

*The Smithsonian roof repairs were planned for six separate buildings located miles apart in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Smithsonian officials attempted to claim that all six rooftops were coincidentally damaged by Sandy. Consider this. An individual filing an insurance claim falsely stating that a recent storm caused damage to a roof already in need of repair could be charged with insurance fraud. In government, it’s merely a bureaucratic scam to get a new roof funded.

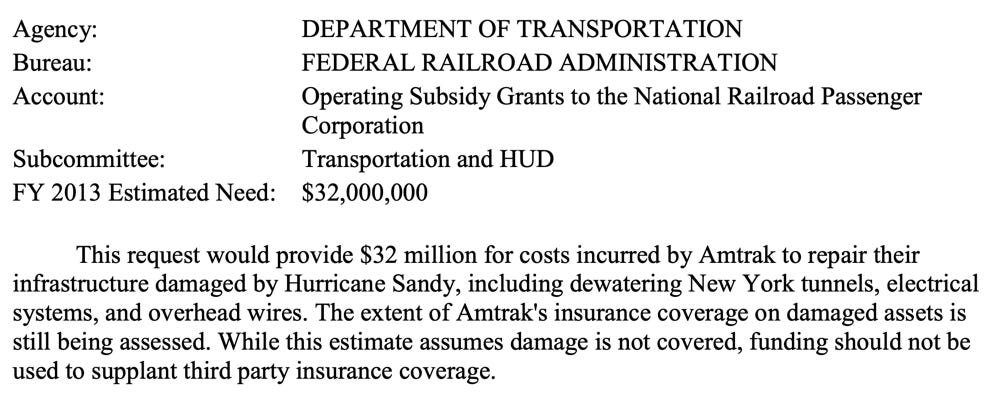

**Amtrak received $118 million in the bill despite the fact Obama’s OMB requested just $32 million to effect Sandy-related repairs.

Congress padded the president’s Amtrak request with an additional $86 million “to advance capital projects.” These costs were not Sandy-related nor constituted an emergency. Such spending requests should fall under the regular appropriations process, and not be misrepresented as emergency or disaster repair costs. Amtrak President and CEO Joe Boardman acknowledged the non-Sandy related monies would be spent on Penn Station and tunnel upgrades, not facilities damaged by Sandy.

***Only $13 million (3% of the NOAA appropriations total of $393 million) were for disaster repairs.

The other 97% -- $380 million ($20 million + $360 million) -- while possibly legitimate expenditures, were not to repair or replace damaged equipment or facilities. This more than a third of a billion dollars in spending should not have been included in an emergency disaster relief bill. The appropriate vehicle would have been the annual appropriations process.

****A little more than $2.9 billion doled out to the Army Corps of Engineers was neither an emergency spending requirement nor Sandy repairs related. The money was intended to reduce future flood risks. Again, another expenditure that should be debated during the normal appropriations process.

Supporters of the spending bill may try to argue that a few hundred million dollars here and a few hundred million dollars there do not constitute a significant misuse of the disaster relief appropriations process. But does the amount of the abuse even matter? Isn’t abusing the system still wrong no matter the size of the dollar amount? Of course, the answer is “yes.”

Despite their minimizing “only” a few hundred millions of dollars, supporters of the pork-laden Disaster Relief bill cannot explain away the whopping $16 billion, or nearly one-third of the bill’s entire total, that was earmarked for the Housing and Urban Development.

That money would go to HUD’s Community Development Fund to be used as block grants to states. The money would be available for expenditure for nearly 5 years for Sandy-related spending, as well as other events that occurred in years 2011, 2012, and 2013. Weather events that occurred nearly two years prior to Sandy, and did not warrant federal hand-outs when they occurred, were now considered “emergency” spending under the Sandy/disaster relief funding bill.

How were these HUD grant funds distributed and was the money spent wisely? No one may really know. Each of the 61 entities that received disaster relief funds were required to adopt an internal control plan to ensure funds were properly spent. However, more than one-third of the entities had established only partial plans (11 entities) or adopted no internal control plans whatsoever (12 entities). The failure to have a complete or any internal control plan increases likelihood those 23 entities had no way of knowing if their disaster relief funds were properly spent.

Several reviews found disaster relief monies were spent improperly. An audit found New York City “disbursed $183 million to the city’s subrecipient for unsupported salary and fringe benefits, unreasonable and unnecessary expenses and did not adequately monitor their sub-recipient or sufficiently document national objectives.”

Visiting Nurse Service of New York, a Community Development Fund awardee, misspent more than half of its $4.8 million grant on inappropriate expenses that were not Sandy-related.

There was no shortage of misspent monies. An Office of Inspector General for the Transportation Department audit through December 2020 found the Federal Transit Administration disbursed more than $6.8 billion to various New York, and New York-area, transportation agencies for disaster recovery costs. However, only $5.6 billion were approved costs. Questions remain about the unapproved $1.2 billion in disbursements.

I found this fascinating. The city of Minot, South Dakota was given $35 million from the disaster relief legislation on top of $67.5 million in federal funds it received in 2012. The money was granted in response to Mouse River flooding that occurred in June 2011. The flooding did not constitute a federal government emergency spending need in 2011, but it did two years later.

There are other problems that arise aside from improper or misleading spending. An all-too-frequent problem with massive disaster related appropriations and how that money is doled out is the eye-popping amount of fraud and misuse that occur.

The Abuse. The previous hurricane spending appropriation was after Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. According to a GAO investigation, as much as $1.4 billion of the money appropriated for Hurricane Katrina was fraudulently spent. Examples include the purchase of NFL tickets, divorce lawyer payments, and buying “Girls Gone Wild” videos.

A Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General investigation determined FEMA improperly awarded $216.2 million in Katrina disaster recovery funds to a single school district in Louisiana. The OIG further found that FEMA awarded more than $2 billion to the city of New Orleans for ineligible work.

Lessons from Katrina were not learned on properly managing funds when it came to Sandy. The Federal Transit Administration was awarded $10.9 billion in disaster relief funds. A Transportation Department Office of Inspector General investigation found that less than half of that amount ($4.3 billion) had been disbursed more than eight years later. So much for urgent emergency disaster relief needs.

Another investigation found the state of New Jersey may have improperly spent $43 million in Sandy housing relief money. Along with New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie was one of the loudest voices claiming disaster relief funds were urgently needed for emergency repairs. However, Christie was accused of doling out “$6 million in Sandy relief money to a project in Belleville -- a town with little Sandy damage, but a valuable political ally” and withholding Sandy money for another community in need as retribution to its mayor.

New York state, according to yet another investigation, was awarded more than $12 million for ineligiblespending.

The federal government has a long-established process in place to assist those impacted by storm events. It is used often. But it should be limited to actual emergency and disaster spending. It should not become a grab bag free-for-all to load up with questionable spending, and monies that should go through the normal appropriations process.

Wait, you might say. You recall an organization or two claiming that all or virtually all of the money in the Disaster Relief Appropriations bill was properly spent on Sandy and related disasters. Were they wrong, you ask?

Absolutely. They were. They were dead wrong. But whether they were wrong due to laziness, incompetence, or for dishonest reasons will be addressed in the follow-on essay, The Shame of Sandy Spending II.

Mark Hyman is an Emmy award-winning investigative journalist. Follow him on Twitter, Gettr, and Parler at @markhyman, and on Truth Social at @markhyman81.

His books Washington Babylon: From George Washington to Donald Trump, Scandals That Rocked the Nation and Pardongate: How Bill and Hillary Clinton and their Brothers Profited from Pardons are on sale now (here and here).